Looking through glass at the merging of body and technology

As a glassblower I often work in close connection to my materials, shaping the hot glass with my breath and movement, keeping me present and alert. This bodingly situated reality contrasts with living in a society that is filled with abstraction and confusion, due to emerging technologies such as AI. It is this complex societal change that forms the foundation of my creative practice-based research.

AI generated image “Create a installation in glass about the neagtive aspects of AI”

AI generated images “Create glassart about the human need for care”

Abstract

At this moment in time, emerging technologies such as AI seem to enable extreme regimes to shape any narrative, and reinforce it with vivid, imaginative imagery. Both the present and the past are being reshaped and manipulated, creating a highly unstable, conflict-ridden and violent time.

Craft-based artists have a long history of engaging with new technological developments to sought to understand their significance for societal changes in their time. Over the past century, the Arts and Crafts movement, for example, have criticised industrialization and machinery. John Ruskin (1819-1900) strongly advocated for craftsmanship and professional expertise over mass production. He argued that quality and individuality represented by craft could never be replaced by machines (Langley Sommer 1995) And though it didn't stop industrialization, the movement has had a lasting influence on architecture, design, and decorative arts, inspiring movements like Art Nouveau and the Wiener Werkstätte.

But even though there has been strong criticism of industrialization, machinery, and robots in applied arts, there has also been a strong attraction and urge to explore new technology. Craft practitioners have increasingly adopted both electronic and digital technologies in their making in recent decades, and the fine line between traditional handmade craftsmanship and high-tech creativity has become blurred.

Looking back, craft both push against new technological developments and is part of them at the same time. The relation is complex and ambivalent. The same type of ambivalence between fascination and frustration, and creativity and critique is something I have experienced in my approach to new technology, and it is something I use in my own research.

The complex experience of shaping glass with my breath and body in contrast to shaping materials with computer-based tools has become the basis of my studies. I am interested in the relevance of craft in a technologically driven society, and what role craft has to play in connection to the societal shift emerging technologies are creating.

ARTISTIC PRACTICE-BASED RESEARCH – QUESTIONS AND METHODOLOGY

My methodology draws inspiration from practical knowledge (Bornemark 2019), where my skills and experiences as a material-based artist form the foundation of my analysis. My method has been to use traditional techniques for shaping glass, such as glassblowing, together with 3D printing and experimental computer based tools such as AI-generated imagery.

I study how craft’s sensory and embodied nature contrasts with digital detachment, and I discuss how these dynamics affect me, and in a wider discussion, how emerging technologies influence a general understanding of reality, along with the ensuing political consequences.

My methodology is exploratory, concept creating and openly curious. I am particularly interested in how my practice based research effect my own understanding of where my material based craft practise start and end, and thereby where my own body and mind start and end.

The discussion about the merging of the body with new technology follow me in my sculptural works, where glass and metal have come to symbolize the meeting point between body and technology.

Methods and Conclusions

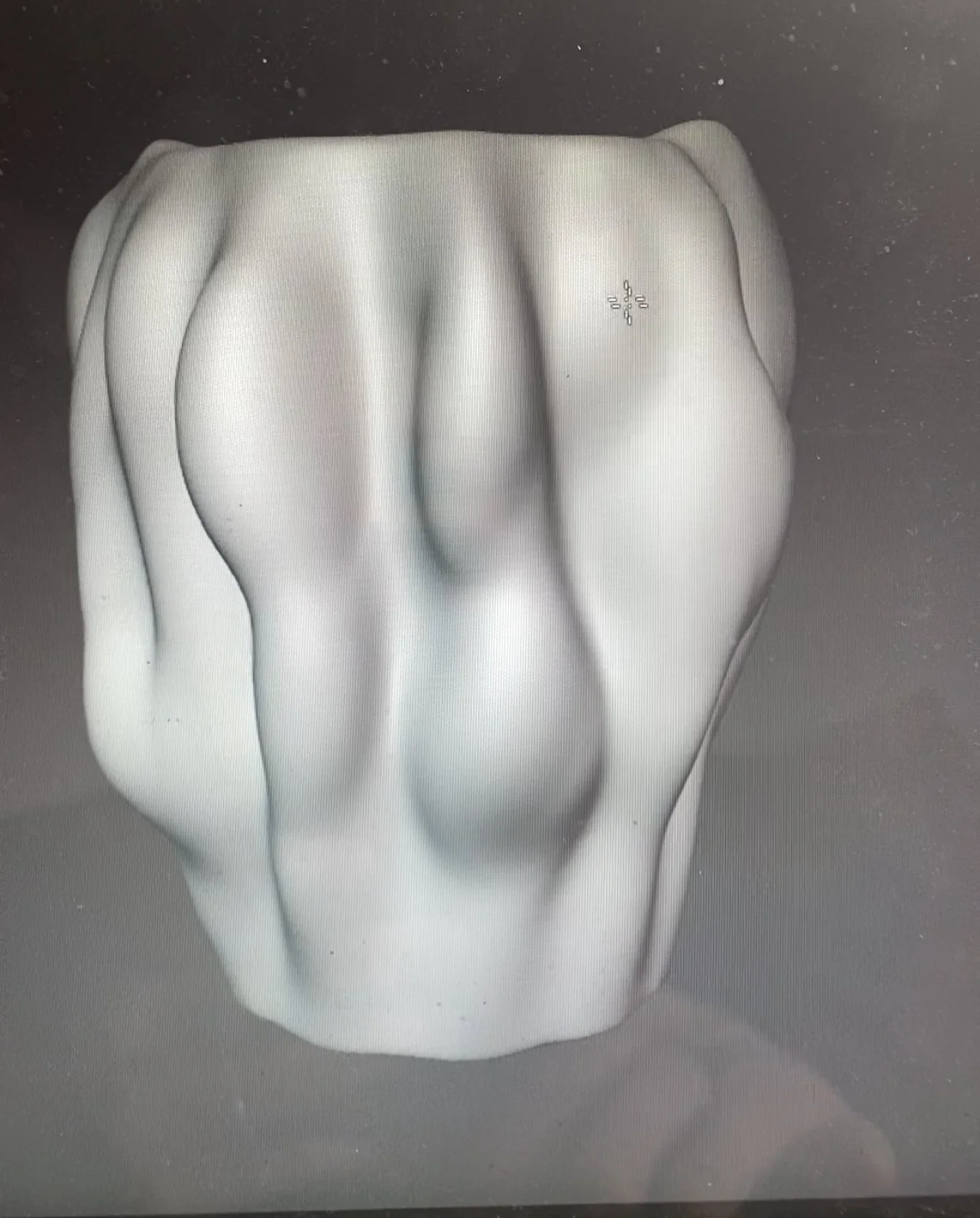

In my artistic practice, I have been working with the 3D creation software Blender for several years. I became curious about how I could use Blender to sculpt in ways that resemble my processes with wheel throwing and glassblowing. I have 3D-printed shapes and used them to create plaster moulds for slip casting and glassblowing.

As an extension of my work with 3D-printing sculpted vessels I have let my materials move between the physical and digital worlds. Though scanning, recreation in Blender, printing and interpreting the objects in AI-based image-creating tools, I explore how my objects can transcend the boundaries between the physical and digital realms.

The use of computer-based tools can be seen as just another technique in the craft process, but from my experience it goes further than that. It raises questions about the start and end of the body in craft. I use the concept of intra-activity formulated by Karen Barad (Barad 2007) of how bodies are not objects with inherent boundaries and properties, but material-discursive phenomena in a material dynamic of intra-activity. I discuss the concept of agency and how it includes non-human actors, such as machines, objects, and ecological systems, acknowledging their capacity to influence and shape the world.Another method have been using different image creating tools based on AI to see what general perception of glass art emerged from these images, and if the sculptures could in any way influence my own thinking and creating in glass.

CONCLUSIONS

Through my explorations it became clear to me that our relationship to digital tools, advanced technologies and AI is becoming increasingly intimate and complex. I conclude that the gap between the physical and digital experience of shaping a material is closing. It is not so much a gap, as it is a crossroads, a collaboration, and an intra-action. And while there is immense potential, creativity, and new possibilities in the interaction between humans and machines – and between traditional handicraft techniques and new computer based tools – my conclusion is that it also creates a kind of dissolution in the frameworks through which we perceive and navigate the world. From my experience, using too much technology disconnected me from my intuitive making, my embodied knowledge and my trust in my capacity to control my own creative thinking. Living in our time challenges the traditional concept of the integrity of the body and self. From a philosophical perspective it raises questions about the unique existence of humanity.

An important part of my experimental practice has been transferring objects and materials between the physical and digital world. These experiments illustrates how the physical world is being twisted and manipulated through technology. Images created by AI borrow elements from the real world, but distort them and in many cases they are also based on stereotypical ideas and presented with a glossy shine.

I draw parallels to current changes in our time and what the Canadian author Naomi Klein (Klein 2023) describes as "The Mirror World” – a surreal alternate reality formed by disinformation, conspiracy theories, and digital media. In the same way as in my experiments, this “Mirror World” reflects elements of real-world issues but distorts them, blending truth with falsehoods. Klein argues that this environment promotes confusion, creating a space where people easily get lost between conflicting realities and narratives.

I reflect on how AI is a powerful tool in the hands of totalitarian rules. And as the German philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote, the ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and the distinction between the true and the false no longer exist (Arendt 1951).

Through my experimental practice I argue that contemporary craft needs to critically engage with contemporary challenges, emphasizing its relevance in shaping perception and resisting the dissolution of material truth in an era of digital manipulation.

REFERENCES

Arendt, H. (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Barad, K. (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bornemark, J et al. (2019) Att utforska praktisk kunskap: undersökande, prövande och avtäckande metoder. Södertörns Högskola.

Klein, N. (2023) Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. London: Allen Lane.

Langley Sommer, R. (1995) The Arts and Crafts Movement. London: Grange Books.